Caught

By Sara Lippmann - May 9, 2017

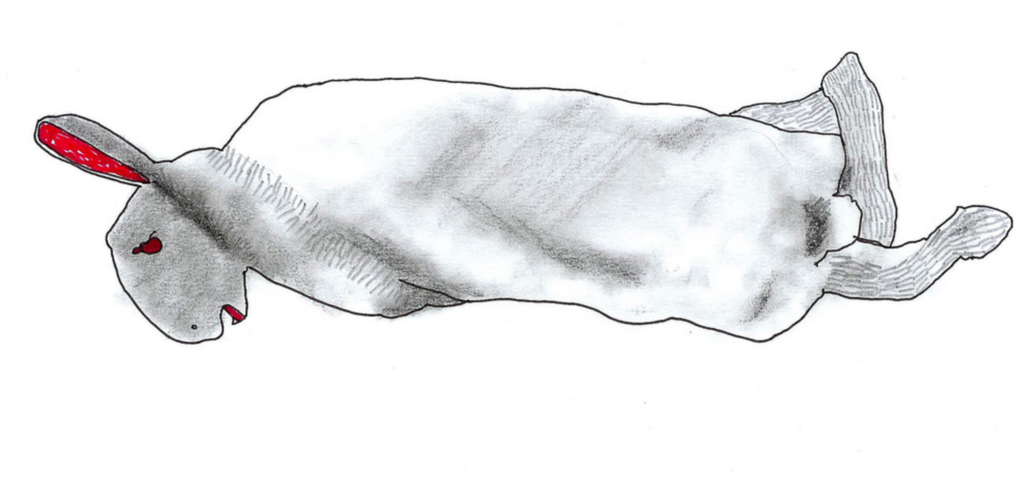

The rabbit family is in trouble. The father – if that moldering mass is the father – has been dead for weeks. Almost unrecognizable in rabbit qualities, body splayed like a lab specimen; fur mangy, bald in spots, black in others, a twist of muscle and bone. The exterminator had been right: Lady, the source is coming from beneath your house. Death, of course, explains away the smell, the plague of flies, with its tidy cycle of decay. Caught between the foundation and flooring, just as he said. Animals get in then cannot escape. The exterminator had snapped on blue gloves, the kind Zach’s teachers wear on bathroom duty, and performed a thorough walk-through, pulling down the attic latch and extracting other mysterious remains – bit of bird, mouse, squirrel – all but ossified, who knows what they once were, or for how long they’d been there. The exterminator was maybe 23. Beth paid extra for removal then fucked him. Before she fucked him, she paid. There was no telling if the issue would persist, if there were holes throughout, the problem systemic in a place this old. The exterminator recommended another guy for that service, but Beth said that won’t be necessary. The house is not ours. We are only renting for the summer.

Now, the summer is over. Doug packs the car. Zach pokes a twig into the foul body. Rabbit guts stick to the wood and he smears it, thick rust, on a paving stone, spelling out the first letter of his name.

“Leave him,” Beth says. “It may be diseased.” Zach drops his instrument and crouches. That’s when he sees it: the small, wriggling, foot wedged in cinder, and that’s when he sees the others tearing through the space between house and ground, a stilted one-foot strip: To the rescue! Mother rabbit first, down the center of the field. An army of rabbits following, ears slick to the wind. Beth squats beside him. There must be fourteen in the herd, in the grass between them and the house and Doug’s calves, brown, strong, and unknowing, suitcases disappearing into the back two by two.

As they approach it is clear: one rabbit falls behind. Another is caught in the mother’s teeth.

“She’s eating him!”

How to explain? Rabbits, beasts. Mothers do this. To the vulnerable, the most frail. They devour the weak; they desert their young.

Together, they watch. The family makes it practically through the other side before the mother aborts mission, drops her young, stopping at the rot to sniff. The straggler bumbles in circles, as if blind. The rest of her offspring are left to find their way beneath the shadow of the house as the mother picks up again, wandering off into a patch of buttercups, to work on her catch alone. The meadow glows in the sun.

Zach slides down on his belly, red shorts and alligator rain boots sticking out behind him. He is almost nose-to-nose with the trapped animal. The trunk slams.

“I got it all,” Doug says, “Is that everything?”

“Not so close. You could be allergic,” Beth says. Most rabbits were hypoallergenic, but she doesn’t want to risk getting Zach sick. Left to its own devices, the animal would not last long. It would be lame. There was no trusting the mother.

With both hands, she nudges the foot free from brick, the flesh bruised and raw where the weight had nearly crushed it. Snaps the lid of her sanitizer hooked to her purse. If Zach were to have a reaction, his face would have blown up like a Thanksgiving Day balloon by now. He is fine. His problem is not animals. Zach scoops the runt into his arms and cradles it, its body trembling, pulsing fast as an organ removed, and she knows what comes next.

“Can we have him? Can we? Can we take him home?”

Beth does not say what home, or whose, or who will care for it, or it could be rabid, don’t get your hopes up, most creatures like this don’t stand a chance. She does not say there is only so much we can do. Sometimes our best intentions only accelerate the inevitable. Human intervention often makes things worse.

“Yes,” she says. “We can keep it.”

*

ART BY FRIDA STENMARK