A Story Narrated by the Boy Who Collects Flies on His Face

By Kit Schluter - Feb 7, 2019

for Jerónimo Rüedi

One waits at night – for what?

What love? Who knows?

André Gide, tr. Anon.

The Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper has a strange, but common, relationship with her Father and Brother. Ask anyone, and they’ll tell you: it’s always been that way; it hurts so much to be normal.

After dinner, during which the Family Pencil jots a few to-do notes on her ankles below the table with its graphite teeth, these large men come pounding at her bedroom door. The Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper does not answer, but floats off to hide, crinkling, in the narrow alley between the wall and her mattress.

Her Father and Brother tumble into the room, accompanied by clouds of a suspicious red sulphur that whisper secrets amongst themselves in a language whose consonants cause even me, the Author, to mistake it for Mandarin. Like snails in a time-lapse film, the men search for her, passing jerkily over every object in the bedroom. Although they are made of human flesh, you may mistake them for paper cutouts, for they do not move their arms or legs as they walk and they are always oriented perpendicular to the surfaces they tread.

They eat the blood-purple apples on her desk; they read her diaries out loud; they laugh at her birth certificate, her first love, who can no longer move or speak because of all the obscene things they have written on her little paper body. They shout, “Come out, come out, Gabby! We only want to write funny old words on your back!” But you should know by now that these words are by no means funny. The words these men want to write are so ugly that they are not even words anymore, but touches. The touch of an obscure sea creature that grows and shrinks with a dead, subterranean whooshing. The touch of the gigantic, amplified fingernails of some undiscovered diamond.

Collapsing with frustration on the bedroom floor, the Father and Brother share bottle after bottle of hard alcohol, and they desperately tear out all the desk drawers, and they build a bonfire and fall asleep beside it, and they wake up shivering when the fire has gone cold. But they never find the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper, because they are looking for her in the form of a heavy, full-grown woman made of human flesh. So they swear to return tomorrow, and they promise to be more successful in their hunt, and they storm out into the hallways of a house I cannot describe for you, for I have never seen it, and the Little Paper Girl has never wanted to talk to me about it.

The moment these large men leave the bedroom, the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper’s mattress lights on fire. She pats at the quickly spreading fire with her little paper hands, but no sooner have they charred than she must give up. So, as every night, she has no choice but to let the bed burn, and burn, and burn.

Through the night the Little Paper Girl sleeps, tossing on the floor, low, where the smoke is thinnest. Waiting for a love that never comes, for this love can no longer move or speak because of all the obscene things written on her little paper body, the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper dreams of another woman, a woman with a gentle voice, a professor made of pencil shavings, who, in a lecture hall, makes fluorescent words appear on a hanging rug with the flick of her wrist. “Once inscribed,” the Professor writes, “paper is never clean. The whiter it gets, the greater the risk your eraser will tear a hole straight through the sheet. I am hungry for oranges! Which one of you kids is going to tell me how to sneak onto the bus that will take me away from this awful city? The palimpsest told me, ‘Bruises are partly yellow.’ And that is why I am not a painter, Frank. I never could have seen that myself. But you, Little Paper Girl, you have to save your household.”

When the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper wakes up, she is on her mattress, which shows no evidence of having burned. The same as every day. She thinks about her dream and reads about the manners in which the skins of various plants and animals bruise. She wonders, how can I save my household? And why should I? Shouldn’t I want to let them burn? The morning passes. The afternoon. Dinner. The Family Pencil and its to-do notes. The darkness of night. Again, the large men tumble into the room, and the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper floats off to hide in the narrow alley between the wall and her mattress, which lights on fire when, in a huff, they storm out into the unknown hallways.

Now, hidden in her desk drawer, the Little Paper Girl keeps the many old things that have, over the years, fallen out of the coat pockets of her Father and Brother. Crawling over to her desk, keeping low so as not to inhale too much smoke, she opens two drawers. From one, she produces a large, white eraser; from the other, the Birth Certificate with Hurtful Words Written on It, her first love, who cannot move or speak. And gently setting her love on the floor, the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper begins erasing these words, which are too hurtful to bear repeating.

One by one, she erases more, until the Birth Certificate begins to stir. Erasing one particularly hurtful phrase with all her little paper strength, she tears a hole straight through the Birth Certificate’s chest. But her love is brave, and this injury, which, for many other sheets of paper would pose a very serious threat, only serves to rouse her. And awakening, refreshed, as if from a three-hundred and sixty year slumber, the Birth Certificate opens her eyes and says, “Little Paper Girl, this is no time to kiss me. First, we have to burn down the factories.” And the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper nods her little paper head. “That,” she understands, “is how I can save my household.”

The city is beginning to waft with an aroma of heroism, which will surely arouse the suspicion of the Father and Brother, so time is precious. Their work must be swift. Together, the two sheets of paper float to the foot of the flaming mattress. And each with one little paper hand clasping the other’s, they use their free hands to pull the bed to the center of the room, closer to the smoky window.

“Wait,” says the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper, suddenly hesitant. “Aren’t there women made of human flesh working in the factories?”

“No,” says the Birth Certificate. “There are twenty-two men present, each made of human flesh.”

“Are these twenty-two men workers?” asks the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper.

“No,” says the Birth Certificate. “They are the company executives, and even their families loathe their very faces.”

“Let it burn,” says the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper.

And after counting from ten down to zero, crouching and taking slow, deep breaths where the smoke is thinnest, the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper, with her first love, the Birth Certificate Who Once Had Hurtful Words Written on It, push the flaming mattress into the once-dreary night from the bedroom window, off toward the nearby factories where, by day, the women made of human flesh are forced to work. The mattress, like a hard, translucent carpet, glows against the darkness of the night, trailed by plumes of benevolent, orange smoke. On contact, the factories turn into giant larvae, which, warmed by the calories of the Company Executives they are digesting, emit a delicious, heroic, scent.

And now, as we watch the factories burn, all the beautiful flies in the world will come to sleep on my face, which I will keep perfectly still, so as not to rouse them. And when, finally, they awake, refreshed, a mere few hours from now, they will fly through the bedroom door to go eat the Girl Who Is a Piece of Paper’s Father and Brother, understanding them to be two great piles of dog shit, the very fresh, wet kind beautiful flies tend to love so much.

_____

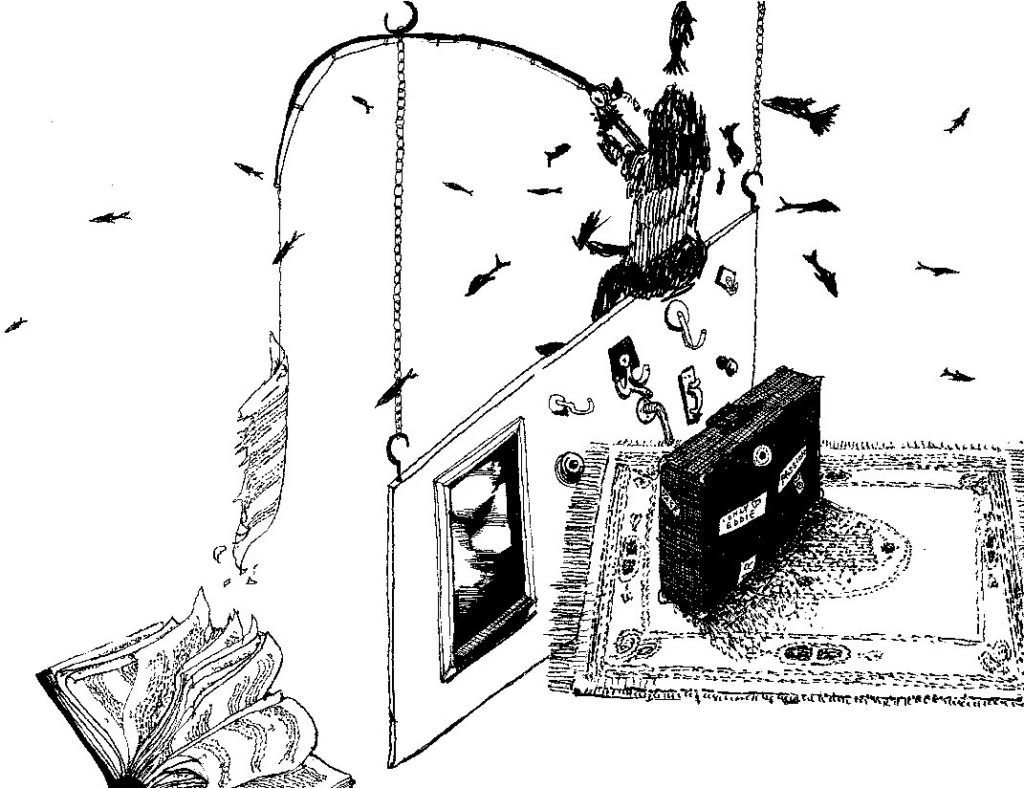

This story is from 5 Cartoons/5 Caricaturas, available here.