Don’t Think It Be Like It Is

By David Fishkind - Jul 15, 2019

After Tony rejected one of my stories for the online publication he’d invited me to submit to, I didn’t have much interest in sending him another. For one thing, I didn’t have many others on hand. Believe it, I’m not made of literature. For another, the one I’d sent him I thought had been a pretty good story.

His i read your piece and liked it a lot, but i don’t know if it’s right text soured all the more as it directly followed his happy birthday david text.

And though I will concede the day was also his birthday, I remained butthurt. The conditions of that Thursday, looking into my phone, waiting for a urinal at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, reminded me only of a rapid descent toward early middle age, a cumulative lack of accomplishment, and that Tony continued to be some number of years younger than I.

I’d grown bored of myself. Eventually I’d have to endure a ninety-minute subway ride back to my two-room apartment at the southernmost point in Brooklyn. I felt capable of imagining why someone might want to tell me i like your work a lot and want to publish you on that website, but it was proving difficult to care.

By and by, I was granted access to a urinal. I employed it for all it was worth. I washed my hands and wished Tony a happy birthday and promised to think of something else to send.

Then I proceeded to try to forget everything.

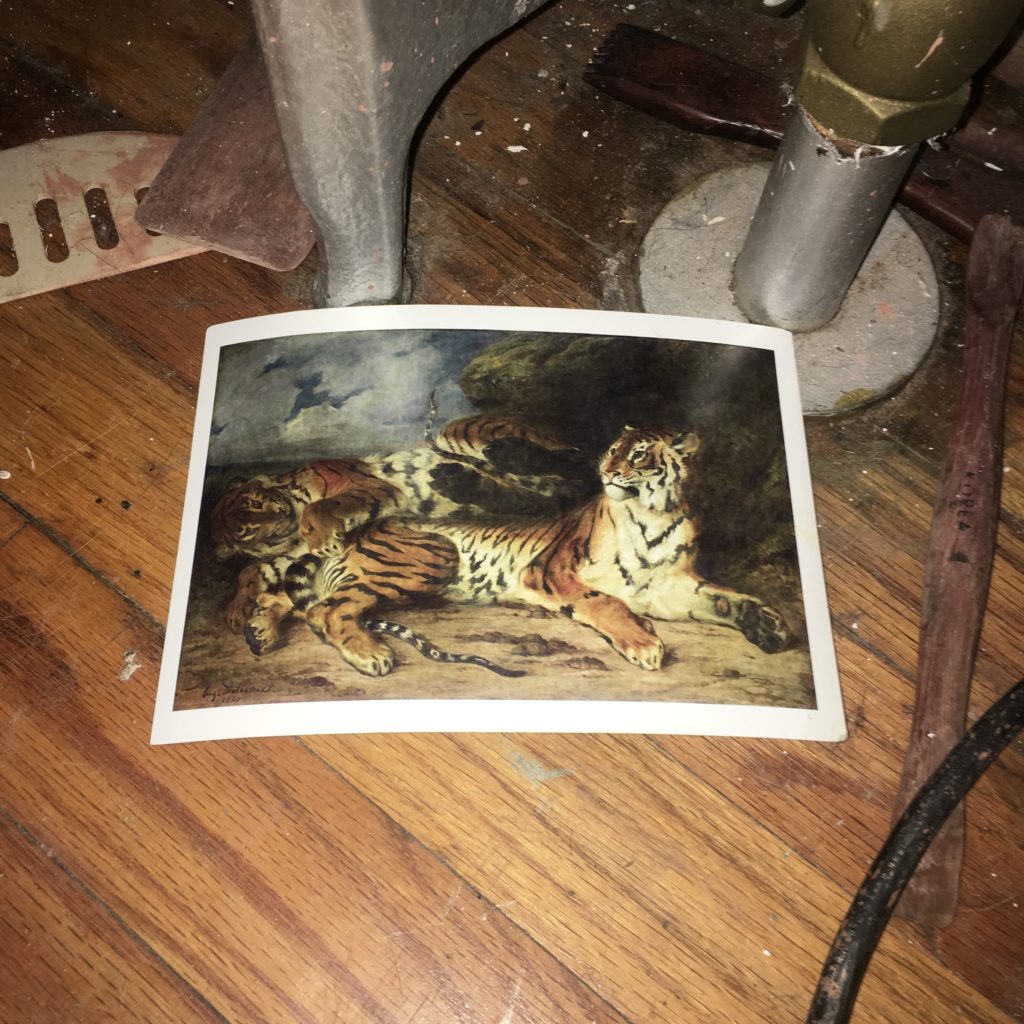

I had a toothbrush in my coat pocket, and I brushed my teeth at the viscous row of sinks. I spent the following couple hours admiring the spectacular quality of Delacroix’s paintings. In the end, I bought myself a postcard, which I propped up on a little shelf at my bedside.

*

Nine months had passed since my intake interview, and still I felt at odds with my personality disorder diagnosis. When in the doldrums, it was easy enough to exploit as an excuse for my problems. But what about the equally protracted stretches of magnetic satisfaction?

By the time the new year rolled around, I was immersed in the latter. The kind of nonchalant stability and confidence that caused me to question if I was otherwise making those supposed histories of unendurable pain more than they were.

I’d allowed my beard to grow in with designs of self-pity, but all I’d ended up doing is looking handsome. My therapist suggested we start seeing each other on a biweekly basis. Plus I’d successfully forgotten about submitting a story to Tony’s publication.

It was the middle of the week. Melissa and I sat in a trendy cafe, stirring coffees. Her boss had recommended her for the position of head baker among a series of rental cabins at the base of Denali, a little more than three thousand miles from the Lower East Side. We perused the online application form on our phones.

―She said if you work there long enough, Melissa said. ―You inevitably serve a few bear mauling victims.

―I’m afraid, I said, dropping my spoon on the floor. ―That if I ever get a real job again… I don’t know. What’s a bear mauling victim like?

Melissa shrugged, and the sole employee at the cafe brought me a new spoon.

Soon, my friend and I were swiping through our respective dating apps, making comment on each other’s prospective lovers. Melissa pointed to one of the men at a table across the room, then showed me him on her phone’s screen.

―What should I do, she said.

At six o’clock, the men left. We had the place to ourselves. The coffee was bad, but the ambiance wasn’t.

And the sole employee looked familiar.

It occurred to me that she might be the person I’d mistaken for a woman I’d matched with on the dating app several months prior, and who worked at a trendy movie theater around the corner. I’d messaged this prospective lover to let her know I’d be attending a particular showing. There, I’d made some reference to the person I assumed was her.

―What, the woman at the box office had asked.

―Never mind, I’d replied.

Everyone on the dating app looked the same. And when she came around to inquire about how we were doing, I asked the cafe employee if she worked at the theater.

―I used to, she said. ―Or, well, sometimes I still do, I guess. In case you see me there again.

She went on to reveal she had several jobs, all at trendy little places around the neighborhood, and all in rotation of informing her that her services were no longer necessary or that she was altogether essential in holding the operation together. She was accustomed to being identified from them.

―One guy saw me at three different jobs over two days. He accused me of stalking him.

―What did you do, Melissa said.

―I told him I was the manager, but he didn’t believe me. He said he was going to sit and wait till the owner came back. The thing is, at that place, the owner and the manager are the same person, and a lot of the time she’s off in Europe or L.A. or somewhere, and he was just sitting there at the only table, ripping up cardboard coffee sleeves into tiny pieces. I told him he’d have to leave, and things got dicey. Some skaters helped me out, though. I haven’t seen him since.

She glanced at the clock over her shoulder with wistful reverence, then sat down at our table.

―Oops, she said.

She stood up and went to mess around with the espresso machine.

―I think I know the place you’re talking about, I said. ―It has a lot of, like, boutique magazines?

―That’s it, she said.

And Jessica turned out to be a terrific conversationalist, engaged and kind, a high school dropout Capricorn with a six-day-a-week schedule and a Polaroid of a Siberian Husky in her apron. She let Melissa and I know a thing or two about Alaska before delivering our bill, and I wrote my number under my signature.

―If you feel like doing anything on your day off, I said.

She texted me later that night.

*

We met at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Jessica was late, and I kept looking for the top of her head. I couldn’t remember how tall she was.

After a while, I pretended to study a map. She came up in front of me, and we hugged through our coats. I’d prepared two topics of conversation: if she was a Capricorn, had her birthday just passed, or was it quickly approaching, and why had she dropped out of high school?

We covered both within the first half hour, wandering through nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European paintings and sculpture. Jessica had lived in the city for two or three years, but she’d never been to the museum.

―I’m not really attracted to museums, she told me.

We had entered a little room with a square Picasso painting of a woman’s head I sometimes liked to spend a few minutes staring at, breathing through my nose. I wasn’t sure what to do.

―Do you like, um…

I trailed off, imagining what the woman in the painting might’ve thought about people who’d quit drinking after trying to drive their cars over the Belt Parkway median at five a.m. on a Sunday morning nine months earlier.

―Where do you stand on aliens, I said.

―Like, do I think that we’ve made contact with them, Jessica asked.

―Just, like, whatever you think about them. Whatever you want to say on the topic.

―Hm, she said.

―It’s also okay if you don’t have anything to say, I said.

―I’m thinking, Jessica said.

Her birthday was in four days. She’d dropped out of school because she felt she could learn everything she needed to know by osmosis. And standing in front of the Buddha of Medicine Bhaishajyaguru, she made reference to a man she was in love with.

I knew him by name. Only a few years before, I’d informally entangled myself with a handful of not-dissimilar women who’d each found occasion to wrap their tongues around that single syllable.

I’d looked into him, but we didn’t look much alike. Our senses of humor and other sensibilities, in terms of how we presented ourselves on the internet, seemed fairly antithetical. And where I exposed an inexhaustible series of reflexive, neurotic digressions in the form of thinly-veiled autobiographical fiction, he played guitar in a band.

Back then, it had kept me occupied till mornings, turning over dubious narratives and unwarranted comparisons, sifting through blogs, social media, interrogating mutual acquaintances of his whereabouts, and double-taking every sunken, healthful face I came across.

Later, I’d gotten involved with a woman who’d never heard of him. This put my obsession to an end, and later, that too had ended. Time bore its ameliorating effects. Admittedly, I’d come to relish any word of this mysterious foil. I told Jessica, and she actually gasped.

She insisted on texting him, and we sat on a bench in the green glow of the north-facing wall, awaiting his response, which wasn’t long coming.

―Huh, Jessica said. ―Phil’s never heard of you.

*

On the walk to the diner, I struggled. Wind burbled, and I leaned stiff toward Jessica’s remarks on a sculpture of a stag adorned with glass, tumor-like apparatuses, attempting to bury my suspicions she’d been deceived.

As things stood, my personality disorder could make no room for the possibility I’d ever been forgettable.

―Cancer, Jessica said.

The sun hadn’t quite set. The Upper East Side basked in a carbon-papery mist. Jessica’s phone rang, and she declined the call, and when our four side orders and coffee arrived, I wanted to say something useful. Instead, I announced I was feeling old.

She asked how old, then got a little sulky.

―That’s the same as Phil, she sighed. ―He said I was too young for him.

I asked did she mind if I peppered the coleslaw. Jessica touched my hand. I should divulge, at the trendy cafe I hadn’t been able to suppress the vanity of alluding to my loftiest aspirations. And so could I reasonably be annoyed with her for wanting to know more about my writing?

―I can’t help thinking of Oscar Gamble, I said.

She looked confused. I shook my head and reminded her about the restaurant job in Alaska.

She said she’d taken an independent fiction workshop in San Francisco the previous summer. Through it, she had a standing offer with a small press I was familiar with, if only she could sit down and write the thing. She asked was I familiar with the work of Frederick Barthelme.

―I don’t mean to be disrespectful, I said. ―But who told you about Frederick Barthelme?

I took a sip of water. And Jessica had a list of books compiled for her by a poet she’d met at a trendy bookstore in North Beach. She was a bit in love with him, she confessed, and, when pried for his name, articulated it in almost three syllables.

―Tony, I repeated.

I said his surname, and she laughed. She took out her notebook and showed me the list in what I assumed was his penmanship, and which included a novel by Mary Robison. I tried to imagine how a Mary Robison character might navigate the banal and insidious associations I was experiencing.

―He gave me his number, and we met for a drink, and then we ended up talking all night at his apartment. We knew a bunch of the same people, like my professor who offered the book deal, and it was all very bewildering. In the morning I had my flight back to New York. But, like, the following weekend, my friend asked me if I wanted to go to San Francisco for a couple days, and I was, like, why not, so I did, and when I told him I was back in town, I think I freaked him out, because he ghosted me and we haven’t really talked since.

―Did he draw you a self-portrait, I asked.

She turned to the next page.

We gave the doodle thorough examination. It, like many others I’d seen attributed to him, depicted almost a silhouette. Abrupt, folksy outlines of a mustache beneath a pair of glasses. He’d given me a business card with a similar drawing on it after we’d met. I ran my fingers over the stationary, exploring its banks and fissures.

I told her I owed him a story, and we continued going through her notes.

*

It was my great estimation that one shouldn’t sneeze in the direction of a trendy cafe unless keen on inheriting a shortlist of common histories.

In another hour, we’d discovered more than enough synchronicities to call stuff uncanny, and I was ready to get home. We put our knuckles in each other’s mouths. I tried to account for my artlessness, but all Jessica said was, ―Phil recently stopped drinking too.

She positioned her hand in my coat, stroked my ribcage through my sweater, and I rode the ninety minutes back to my apartment.

There, I sat on a Moroccan rug I’d bought off my friend’s ex-girlfriend and googled photos of Denali and the aurora borealis. I watched a video about UFOs. I closed my eyes. I hated to think of waking up.

*

Three days later, a construction project commenced on a vacant lot down the block. Bulldozers arrived. They ripped craters in the earth. A crane was delivered on the bed of a truck, and come afternoon, it was erect, affixed with a pile driver, which fell every one to two seconds, sending brief, acute quakes through the neighborhood.

I watched the leaves of my potted plants vibrate. I went to a dinner party and sat by the window, opening and closing it at the hostess’s request.

―Your beard, she laughed. ―I never thought of you as actually turning into a man.

Had I still been going to therapy on a weekly basis, I’d have gone that morning. But I hadn’t. I took a picture of the hostess’s cat. It had a Tupperware lid tied to its head.

―How was your date, Melissa asked.

―Um, I said.

I forked a soft, bisected length of glazed carrot onto my plate.

―I actually don’t know.

―Oh, you should text her, Melissa said.

―But not after ten o’clock, the hostess said. ―Anyone who texts after ten o’clock is, like. That’s entering sordid territory.

―What do you mean, I asked.

―You know what I mean, she said.

At eleven, I texted Jessica the photo of the cat, and the next afternoon we had another date.

We strolled through rows of caged pit bulls, hopped over puddles of urine and vomit. Between animal shelters, Jessica reclined the Buick’s bench seat, languishing in the throb of rush hour traffic.

―I’ve been thinking about what you said, she told me.

I wasn’t sure what she meant.

I’d been trying to make sparing use of my car. Yet I could think of no other way to get from Bed-Stuy to Tribeca to Brownsville and back again. Additionally, I thought it would impress her.

It did. And thus, I began to feel rotten. Like I’d manipulated the circumstances in order to compose myself as more eccentric and charming than I could ultimately keep up with. I knew the scenario well enough.

―Aw hell yeah, I said into the windshield of evening clouds.

She laughed, and I was aware I was wrong. I observed the car ahead of me’s blinker with mounting anxiety. My facial hair had grown coarse. The Buick leaked power steering fluid, issued grisly whirs. At a red light, I got out and kicked its tires.

Jessica looked through a pile of burned CDs on the floor and put in a mix the woman who’d helped me forget about Phil had made, which included something by Bright Eyes. I heard an ambulance siren behind us.

―What’s wrong, she said.

―What?

―Your face.

Jessica appeared to choose her words.

―You looked really angry for a second.

I apologized, a little stunned.

―I am a person capable of hideous rage, sincere rhapsody, and blindsiding indifference, I whispered.

―What, Jessica said.

―I just really like Bright Eyes, I said.

*

It was dark out when I dropped her in the Lower East Side. I declined to join her friends for karaoke. Though aware it was her birthday all along, I’d failed to reconcile my endearment with the cloying shame of why she’d squandered so much of it in my company.

Jessica had suggested the shelters. At each, she’d maintained an intention to adopt some new pet then and there. It struck me that perhaps my private assumption she wouldn’t had seeped into the ether.

―Well, she said, ―I’m going to be out of town for a little while after this weekend.

―Oh yeah?

―I’m going to California. Phil’s band is on tour, and he said I could tag along.

―I thought you worked six days a week.

―I do.

―That’s great, I said. ―I’m going to be gone too. I’m going to Mexico for a wedding.

―You are?

―Yeah.

―Well, right here is fine, Jessica said.

But as she was gathering herself, a cop car addressed us through its intercom.

―Move your vehicle, it commanded.

I pulled up another fifty feet to the corner, wedged in front of a fire hydrant with the hazards on, and we started to kiss.

I could feel my disenchantment melt away. In that moment, warmed by the rattle of the heater, the hiss of the leather as we rearranged our bodies across it, I could even see a future emerge.

―I think you’re getting a call, Jessica said.

She looked in her bag and smoothed her skirt, then wrestled with the passenger door.

―It sticks, I said.

I’d purchased a decal and keychain while she was in the bathroom of an ASPCA, but I’d neglected to give them to her. I waved through the window, phone in hand, before answering it.

*

I had almost forgotten about Mexico. Two days before my flight, the Buick’s brakes went out and I drifted into an empty intersection.

I took a hot bath to deal with what incurred thereafter. I shaved my beard to a mustache. In part, I had not wanted to show up at the wedding so unkempt. More selfishly, however, I couldn’t help taking advantage of the opportunity to affect some provisional eccentric charms.

I called my therapist to say I’d be missing our session.

―Try not to think about…

Her voice cut out.

―Wait, I said. ―Can you repeat that?

I watched a squad car stall in a handicapped space. The cop, Uzi strapped across his chest, attempted to engage the engine with single-minded fury. After a while, he got out and spit on the dusty asphalt. Smoke had begun to ripple from under the hood. He regarded it, arms akimbo. He typed something into his phone and abandoned the vehicle, keys in ignition.

I, on the other hand, slept in a stony room with a wolf spider and a crucifix. A wicked half moon, sliced sideways, melonesque, hovered over pitchers of horchata and fried cockroaches. And we ate these with nopales, wrapped in tortillas, covered in mole sauce. We sat out late in the tepid, dry air, listening to the howls of feral dogs bounce against the cliffs of Tepoztlán.

My friend was married on a Saturday. We’d been roommates in a squat-like arrangement several years earlier, and so our accord was marked by its distinction from more complex, intimate networks. The sole guest I’d been acquainted with was her musician friend, drummer in a band I’d gone to see Phil’s band open for during that period of my entanglement with the aforementioned not-dissimilar women. Naturally, I’d been paranoid, and things had come to a head after he’d appeared at the door later that night to crash at our apartment.

The musician did not seem to recognize me, but when I introduced myself, he took my arm and pulled me into an embrace.

―I’m sorry, I said. ―I was drinking all the time back then. I was so angry at being alive. I’m sure you’ve got your own opinions. I mean, all that shit with, like. With Phil. Do you remember him? It’s been over for a while anyway. I met a woman. She woke me up at four a.m. the morning after my birthday, not this past birthday, but the one before, and, like, she ended it. But it was actually for the best. I mean, stuff is only getting better.

I might mention that by then we were both on substantial doses of MDMA, provided by some of the groom’s close friends.

―When’s your birthday, he asked.

―December twentieth, I said.

The musician threw back his head and laughed. He grabbed my shoulder, looked at me with dark, pupil-filled eyes.

―That’s mine too.

*

When I arrived home a week later, I found I couldn’t unwind. I stayed up pacing, seeking nothing. I reversed my sleep schedule once and back again. I ignored Melissa’s text messages, defaulted on the car repair payment, took some freelance work, flaked on it, and sent the resulting emails to my spam folder. The pile driver fell. My apartment shook. I googled alien abduction testimonies. I waited for the other shoe to drop.

Trimming my mustache, I was racked by dread. I closed my eyes amid a flash of Tony’s portraiture.

We’d met at a writer’s conference, where I was giving a reading. Less than two years had passed, but that entire landscape, one of now incongruous-seeming hope, momentum, and utility, had since been painted over with stark perplexity. Then, I’d just finished work on a novel, the publication of which I’d been assured would change my life. I was pre-diagnosis, drinking in moderation. The night before, I’d gone on my second date with the woman who’d never heard of Phil.

And I don’t know how it had come up we had the same birthday, but in the time that followed, I’d probed into more drawings of Tony’s than poems. Finally, I’d come to share their likeness.

I googled what day it was. There were six more till therapy. Something I’d written on a Post-it note and stuck to my fridge said, The answers we don’t have are the things that free us. But I couldn’t remember the context.

I drove to Plum Beach.

―Does anyone know, I said over the phone, to a docent at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I was looking at the slack, fragrant water, the glimmering trash and oiled iridescence separating the boroughs. I looked to the sky.

―Can anyone tell me, I said. ―Does anyone have any earthly idea if those three fluorescent lamps affixed to a particular overpass, observable from the eastbound tract of the Belt Parkway, are, in fact, a Dan Flavin?

*

A month or so after Jessica’s birthday, Tony texted, inviting me to submit a story to the online publication he was editing.

I thanked him for reminding me. I told him I’d poke around. I told him I’d asked out the server at a cafe I’d been having coffee at about a month prior.

we went on a couple dates, I texted. she was nice. turned out you guys had had a little love affair, i put two and two together when she asked if i was familiar with frederick barthelme

hahah, he replied. was it jessica? she gave me her number while i was working at that bookstore in sf

I confirmed, and he said he was tickled pink. Still, that night, I looked through what I had on hand, and it turned out I didn’t have much.

A toilet flushed in the apartment below mine. I brushed my teeth. I washed my hands.

In the morning I walked past more gaping holes in the street. The construction project had extended several blocks beyond mine, but without vertical progress. It advanced only further underground. And I was careful where I stepped, as I made my way along the southernmost avenue in Brooklyn to the sliding scale counselling center that accepted my insurance.

―How are you, my therapist asked.

―I’m good, I said.

―Is there anything you want to talk about?

―Hold on, I said. ―There must be.

When I got home, I emailed myself a sentence about one of my stories being rejected by an editor named Tony who shared my birthday.

The following afternoon, I pasted the sentence into a word document. I highlighted Tony. I replaced it with Will.

I was almost ready to type something else when my phone vibrated.

Jessica had texted, Hey want to go to the met again this week if you’re free?

I told her I did. But I didn’t, and cancelled the next day. I wasn’t sure why. I said I was sick, which was true enough, would always be true enough, but I was determined not to become the person who freaked out and ghosted her. I was determined not to take my own cue.

And I wasn’t freaked out. Quite the opposite, really.

I wanted to stop believing there were secret passageways that might excuse everything I’d discovered, but I didn’t want to believe I couldn’t keep making them up.

*

Some number of nights later, I drew a hot bath and shaved my mustache. I’d been worried about the misleading narrative I was proliferating. Almost two months had passed and not a single photo had pierced the dating app.

I took my phone out and swiped through.

I matched with someone. Shortly after, she messaged, i think u know my friend jessica she regaled me with stories of dog shelters and nice drives

funny, I wanted to reply. i just used regale in its gerund form, writing this story in which she appears as a fictionalized character, under the name taylor

Instead, I sent an aw hell yeah and left it at that.

At this point, I already knew I couldn’t escape anything. At a different point, I’d thought by then I wouldn’t exist. And when I did, and when I encountered more souls inhabiting further divine cells, would it be fair to name them coincidences? I could only try to forget.

In this spirit, I took no umbrage with my response from the restaurant in Alaska. The owner wanted me to know she was moved by my enthusiasm. She rarely had the opportunity to deal with an application so grandiloquently diffuse, and encouraged me to reapply just as soon as I had experience working in the food industry.

I sent Melissa a screenshot of the email. She’d gotten the job, and had been anxious all week deciding whether or not to accept.

She asked me to forgive her either way, and soon we were discussing a date she’d made with the best friend of a man with whom she was informally entangled. They’d matched through the app, and she’d put two and two together in a way he wouldn’t have been able to, due to her relatively cryptic, anonymous online presence.

She expressed concern about the moral ramifications of proceeding under the circumstances.

idk, I texted. what’s the worst that could happen?

So according to quantum mechanics, she replied, two particles that have been near each other, they continue to constantly affect each other no matter how far/separated they might end up……

Melissa texted again, That’s a lil wild

I had no grounds to disagree. But if she wasn’t kidding, then that opened up all kinds of interpretation. Like, for instance, I may actually have been made of literature.

Melissa asked what I was up to, and I told her about the story.

i can’t tell what’s missing, I texted. but i think it’s catharsis

*

As days passed, I went through the manuscript a few more times. I deleted my use of regale in its gerund form. I added new details. I removed things. The pile driver fell like a mantra, and I worked through the afternoons.

When I was satisfied enough, I looked out the window. It had snowed. Just enough so that no surface remained untouched. And yet, it was only a sheet, not a blanket. Nothing had been hindered, and still everything transformed.

this summer is going to be good, I texted Melissa.

i hope by the end, I sent.

I took a sip of water and considered stuff. Then texted, i am an alien living in another dimension

So ugh, she responded. Before you sent that I said that, exactly. I whispered it word for word. I completed your sentence from the m train

I sent her a row of exclamation points.

I know, my eyes watered

i’m grinning, I texted. so sweet

My phone vibrated, but I didn’t look right away.

I walked the perimeter of my apartment, the leaves of my potted plants swaying in the pile driver’s pulse. I felt the floor quiver. I watched the Delacroix postcard topple from its perch. It wafted and alighted face up, gliding to a halt against a radiator.

How long, I wondered, would it have to sit there, heating and reheating against that torrid metal, drying and flickering in the possibilities of physics, to burn?

I love you, I thought.

And I kept thinking it, breathing through my nose, feeling like I was about to hear the end of a joke. I love you. It’s crazy. I thought it to Melissa and the world. My phone vibrated. Other things did too.