Some Cliffs, Which Overlooked Some Sea

By Gabriel Smith - Oct 15, 2018

I was in the waiting room. Then I was in the examination room. There was a chair, and another chair, and a hydraulic doctor bed. ‘Sit down,’ he said. I didn’t know where. ‘Not on the bed,’ he said. I sat on a chair.

‘I think I have a concussion,’ I said.

‘Why do you think that?’ he said.

‘My nephew hit me.’

‘He hit you?’

‘In the back of the head.’

‘How old is he?’

‘My nephew is twenty one.’

‘Okay,’ he said. ‘Take your shirt off.’

‘Really?’

‘Sure.’ I unbuttoned my shirt. He shined a light in my eyes. The light was on the end of a cone. The cone was set at ninety degrees on the end of a metal rod. It looked like a thing dentists use.

‘No concussion,’ he said. It didn’t seem like he could tell that just by shining a light in my eyes. ‘Looks like you have a little eczema there though.’ He pointed to my chest. There was a red patch and what looked like a slightly raised piece of dead skin, a plateau of dead skin, in the centre. Just to the right of where I assumed my heart was.

‘Oh no,’ I said.

‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘It’s treatable. I am prescribing you hydrocortisol cream.’

‘Do you mean hydrocortisone?’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Hydrocortisone. That’s what I said.’

***

My brother’s wife, when I was back at the house, said I shouldn’t have provoked him.

‘He’s very sensitive,’ she said.

‘He’s twenty one,’ I said.

‘He loved your Dad,’ my brother’s wife said. ‘They had a real connection.’

‘I don’t see what that has to do with anything.’

‘Are you really going to wear that outfit?’ she said. I was wearing a t-shirt with lots of ‘Phils’ on it: Phil Neville, the Philippines, the concept of ‘Philosophy’, Philadelphia (the cream-cheese spread), Phil Mitchell, Prince Phillip.

‘What?’ I said. ‘No, I am going to wear a suit.’

‘It has a soup stain, you can’t wear that t-shirt.’

‘I am going to change,’ I said.

My brother walked into the kitchen and kissed his wife on the forehead. ‘You should wear the Phil t-shirt to Dad’s funeral,’ he said, slighly shouting.

‘I am going to change,’ I said, and left the room.

***

After showering I looked at myself in the mirror. This was the house I grew up in. The doctor was right about the skin on my chest—it looked weird.

I picked at it and it came away painlessly. Just a square-inch of skin at first, which kind of hung off my chest and flapped when I flicked it with my fingernail.

I pulled at it again and more skin came away. It was thick and translucent white and looked like the shed skin of a snake I had seen in an exhibit at a zoo as a child.

The skin kept coming. Over my left nipple and up to my armpit. Once it reached my armpit it started to sting a little. I stopped pulling and it just hung there.

Curling my left arm up towards where the dead skin was attached, I pressed down with my left hand and pulled at the dead skin with my right. It came away easily, painlessly. Once I’d torn it all off I had an alarmingly large piece of skin in my hand. Like, half my upper chest, and a lot from on my ribcage. There was a little rift of dead skin left on my chest, poking upwards, almost imperceptible, like sellotape.

I didn’t want to leave the skin in the bathroom bin. I kind of dropped it into the bath — it made a slapping sound when it landed — then turned the shower head on hot and hard, and pointed it at the piece of skin. Mercifully, after a moment, it began decomposing, and tiny pieces of it were carried by the water down the bathtub into the drain.

***

After the funeral, at the wake, at the house, my nephew apologized for punching me.

‘I’m sorry for punching you in the head,’ he said.

‘No problem,’ I said.

‘I just get so angry sometimes.’

‘Really?’

‘Don’t you?’ he said.

I poured myself some more white wine from the bottle I was guarding from everyone else.

The new skin was tender under my shirt, under my jacket.

***

My uncle Harry was in the large living room.

‘Yes, I borrowed it from work,’ he said. ‘From the work canteen.’ He was talking about a large urn that stored and dispensed near-boiling water. ‘I thought a lot of people would want tea,’ he said. ‘And that this would make it easier.’

The general consensus at the wake was that it was a good idea.

‘It must have been hard to get here,’ I said. ‘What with all the water in it.’

‘What? No,’ he said. ‘You don’t transport a full urn.’

‘Oh,’ I said.

‘That would be dangerous,’ he said. ‘A full urn.’

My brother walked over. He was holding a glass of red wine and a beer.

‘I see you have two drinks,’ I said. ‘Nice.’

‘Thank you for apologizing to your nephew,’ he said.

‘What?’ I said. ‘I didn’t apologize.’

‘He really appreciated it.’

‘He apologized to me,’ I said.

‘Sure,’ my brother said.

‘Hey,’ I said. ‘Some of my skin came off earlier.’

My brother was a plastic surgeon. That was his job. ‘What?’ he said.

‘Like a reptile.’

‘Your skin came off?’

‘Like a reptile,’ I repeated.

‘That sounds like eczema. You should see a doctor.’

‘You are a doctor.’

‘I’m not a skin doctor.’

‘You’re a skin doctor.’

‘No, I’m not. I’m a surgeon. I’m not looking at your eczema skin.’

‘I saw a doctor today,’ I said. ‘He gave me a cream.’

‘So use the cream,’ my brother said.

I walked away to get another drink.

***

‘That was a beautiful ceremony,’ our neighbor said. She was older than sixty, and wore purple literally all the time, even to the wake.

‘It was?’ I asked, but she thought I was just agreeing.

‘He would have loved it,’ she said.

‘He would have?’

I thought about my father in the audience of my brother’s school flute recital, holding a biro and the program, ticking off each act that had finished performing.

I thought about my father in the audience of my brother’s school prizegiving, slumped, only sitting up when a small girl, maybe nine, won the prize for ‘dance.’ My father sat straight up saying loudly, so lots of other parents turned around incredulously: darts?

‘Yes. He would have found it very moving,’ the neighbor said. ‘He was a very emotional man.’

‘You knew him pretty well, huh,’ I said.

‘We had a special connection,’ she said.

‘Listen,’ I said. ‘Shut the fuck up, you stupid bitch.’

***

I woke up hungover in my childhood bedroom, still wearing my shoes and trousers. My white shirt seemed to have a little blood on it.

I took my shoes off and went downstairs to make coffee. My brother’s wife was in the kitchen.

‘Want some coffee,’ I said. She didn’t say anything. My brother walked in as she walked out. He kissed her on the forehead as they passed each other.

‘Got some blood on you,’ my brother said. ‘Make me some coffee.’

I sat down at the breakfast island in the middle of the kitchen. The urn was still there. There were glasses and mugs everywhere, the foily remains of wake snacks. I took out my cigarettes and lit one.

‘Jesus Christ,’ my brother said.

‘My head hurts,’ I said.

‘She got you good,’ he said.

‘I should have hit her back,’ I said.

‘She made you look like a little bitch,’ he said.

‘Yeah,’ I said.

‘You are a little bitch,’ my brother’s wife shouted from the other room.

***

In the shower more skin came off. My whole back, and some from my bum too. It came off more easily this time. I blasted it with the shower head and it disintegrated and went down the drain. I worried about my skin building up in the drain and blocking it.

***

My brother drove me and his wife over to our mother’s nursing home. My brother’s wife made a point of me sitting in the back of their car, which was small, but new and expensive-seeming.

‘How was the funeral,’ my mother said, from her chair, which was disgusting.

‘It was beautiful,’ my brother’s wife said. ‘It was a really beautiful ceremony, everyone said so.’

‘I’m so glad,’ my mother said.

‘Have you got everything you need, Mum? Do you need us to bring you anything?’ My brother was talking louder than was necessary.

‘What happened to your face?’ my mother said to me.

‘Cheryl slugged me,’ I said.

‘Whyever would she do that?’ my mother said.

‘I was defending Dad’s honor.’

‘He called her a stupid old bitch,’ my brother said.

‘No I didn’t,’ I said.

‘Oh, no,’ my mother said.

‘And my skin keeps peeling off, Mum,’ I said. ‘I’m very frightened.’

‘What?’ my mother said.

‘Nothing,’ my brother said. ‘He’s just joking. He has some eczema. He’s just joking.’

‘Oh,’ my mother said. ‘I hope you didn’t hit her back.’

‘I got her right on the nose,’ I said. ‘She’s in the hospital.’

‘Oh, no,’ my mother said.

‘No, he didn’t,’ my brother’s wife said. ‘He’s just trying to upset you. He didn’t hit her.’

‘She’s bed bound,’ I said. ‘She’ll never look the same.’

‘Oh,’ my mother said.

***

‘Maybe we should just kill Mum,’ I said, when we were leaving the nursing home. ‘No parents, no rules. Clean break.’

‘Shut up,’ my brother’s wife said. ‘That’s not funny.’

***

When we got back from the nursing home I ate a Xanax. I got a cold bottle of white wine from the fridge and took it to the bathroom. I ran a bath.

I had bought the Xanax on the internet because I read about people taking it on the internet. I couldn’t get it prescribed to me in England. Doctors never believed me.

I lay in the bath for a while and waited for the Xanax to kick. A layer of condensation formed on the white wine bottle. My parents, who were either dead or in a nursing home, had an extremely large, cold fridge in their house.

‘Spent my god damn inheritance on some excellent fridge,’ I said.

Once the water was getting cold — after the Xanax had kicked and I’d drank maybe one third of the bottle — I tried to masturbate. My penis felt loose, and when I raised it above the waterline I saw that the skin on my penis was coming away.

I pulled at the skin, which was tender. In small pieces I tore away the entire skin around my crotch, penis, and upper thighs. I got out of the bath and the skin dissolved as I drained it. I finished the bottle of wine while drying my new and remaining skin.

***

Dryish, I ascended the stairs to my parents’ bedroom and bathroom, which occupied the third floor of the house. I took my Dad’s old bathrobe, made of navy blue towel, and put it on against my naked skin. I descended the stairs, headed for the kitchen.

In the kitchen I made some coffee. I could hear Saturday night television from the other room. My brother walked in.

‘Long bath,’ he said.

‘Sure,’ I said.

‘Dad’s robe?’

‘What?’ I said. ‘Hey, more of my skin just came off.’

‘Don’t wear that,’ he said.

‘The skin all on my dick,’ I said. ‘It just came off.’

‘You sure you can afford to lose those millimetres?’ he said.

‘I’m serious,’ I said. ‘My dick skin.’

‘Like, your foreskin?’

‘No, just the top layer of skin. On my foreskin.’

‘Sounds like eczema.’

‘It really doesn’t seem like eczema,’ I said.

‘I’m not being funny,’ he said. ‘Take off Dad’s robe.’

***

We picked my mother up from the nursing home in their small expensive car. My mother sat up front. She was carrying my father.

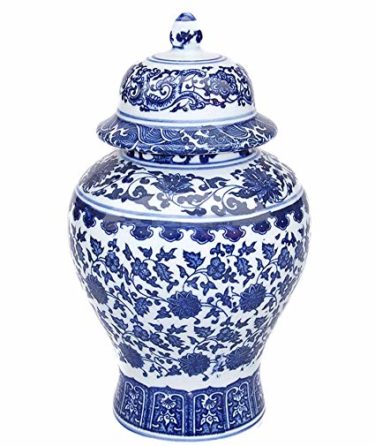

My father had been combusted, at the funeral, and the ash was in an ornate blue and white Oriental-looking lidded vase.

We were driving to some cliffs, which overlooked some sea. It was where my father had grown up, supposedly, but I didn’t imagine he’d spent a lot of time just hanging out on the cliff edge.

‘I made a mix cd,’ I said. ‘For the journey.’

‘Shut up,’ my brother said.

‘It’s called: “Dumping Dad – Volume One.”’

‘We’re not dumping him,’ my mother said. ‘We are scattering him. Can we stop at the next services.’

***

At the services my brother’s wife helped my mother to walk to the bathrooms. I hung out by the car and smoked a cigarette.

‘Can I have one of those,’ my brother said. I threw the packet at him, which he caught, annoyingly.

‘Do you think Dad was fucking Cheryl,’ I said.

‘Who cares,’ my brother said. ‘It’s disgusting either way.’

‘How is it disgusting if they were not fucking,’ I said.

‘Shut up,’ my brother said.

I finished the cigarette and then took the oriental vase from the front seat of the car.

‘What are you doing,’ my brother said.

‘Dad didn’t like cliffs,’ I said. ‘Dad liked service stations.’

‘Okay,’ my brother said. ‘Don’t take much. Leave some for Mum.’

We both took a little handful of dad ash from the surprisingly large amount in the vase. We put some on the steps leading up to the service station. We put some in front of the Starbucks refrigerator where they kept the smoothies and breakfast pots and cold sandwiches. We put some in front of the counter at Burger King, and some on the magazines at W H Smiths. Then we washed our hands, and walked back to the car, and waited for our mother and my brother’s wife to come back from the bathroom.

At the cliffs, my Mother cried as she emptied the vase over the edge into the sea. I could feel the skin on my neck drying out and dying, and I picked at it slightly. I wanted to ask what she would do with the vase, once Dad was all out of it. Would she keep it? Rinse it? Use it for flowers, or leave it empty?

***

In the bathroom, hours later, I picked at the skin on my neck. It pulled upwards, up my chin, then the skin from my face started coming off. I just kept pulling, up my cheeks, around my nostrils, around my eyes and from my eyelids, up my forehead, right up to my hairline, where it tore off neatly, until I had a mask made from my own skin in my hands.

***

When I was back in London, where I live, miles away from my parents house and my family, I went to see a good doctor, a reputable doctor, a Private Doctor, who was paid for by my work health insurance.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I can see what you mean.’

‘You can?’

‘There’s a lot of bruising around your cheekbone. What did you say you did?’

‘That’s not why I’m here,’ I said.

‘Why are you here?’

‘All of my skin is peeling off.’

‘That sounds like eczema,’ she said.

‘No, it’s not eczema. It comes off in huge sheets. My whole chest came off. My whole face came off. I am shedding my skin. Like a reptile. I am frightened. I think I am inside myself and trying to get out.’

‘And what’s under the skin?’

‘What?’

‘What’s underneath, when the skin comes off. Does it bleed?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘It’s just more skin.’

‘So what’s the problem?’

‘Excuse me?’

‘If it’s just the same skin underneath, what’s the problem?’

I told her that I didn’t know.

‘I wouldn’t worry so much,’ she said. ‘It might feel dramatic. But it sounds like despite everything, you’re still the same.’

‘Alright,’ I said.

‘I’m going to prescribe you an eczema cream,’ she said, and started typing on her computer.

‘Hyrdrocortisol?’

‘Cortisone,’ she said. ‘There’s a pharmacist next door, and you can pay the receptionist on the way out.’

‘Alright,’ I said. I stood to leave. ‘Thank you for your time.’

***

That night, my father appeared to me in a dream. He was wearing the bathrobe. He oscillated in size and distance from me, but generally seemed around five feet tall, and maybe ten feet away.

I told him I felt frightened that my skin was peeling off.

He didn’t say anything, he just kind of oscillated, and then the narrative of the dream changed, and I forgot about him until I woke up.