Late-Stage Therapy

By Paul Perkus - May 2, 2017

1

Back in his office my therapist, Dr. Walter, has beshitted himself again. Should we change restaurants? He gets sick every time we go to this Japanese one. I like the waitress, she knows our routine: that we get an extra portion of salad dressing and no-charge pineapple for dessert.

He’s sitting on the toilet looking ashamed. A flap of belly fat covers his private parts. I help him wipe the shit from his pants, breathing through my mouth to avoid the smell. I toss his underpants in the trash and I throw up in the kitchen sink.

I feel abandoned by Dr. Walter’s mental deterioration.

Dr. Walter would try to get me to be more “with it” as he put it. We were walking down Second Avenue one day years ago on the way to the post office and he pointed out this well dressed young woman ahead of us. I checked her out. He says: “Not her ass, but her sense of purpose, the way she walks, she’s getting things done.” I was more of a watcher than a doer, a flaneur, a bum.

2

“Long time, no see,” says May the smiling waitress as Dr. Walter and I settle in our regular booth at Nori Sushi.

It is a warm, sunny spring day. Dr. Walter is exhausted from walking the short block from his apartment building. We stopped using his office across the street in the fall. He couldn’t get there safely on his own anymore. Our weekly lunch therapy sessions were held in his apartment during the cold months. Either ordering up or dining on pancakes or egg and cheese sandwiches prepared by his home health aide.

Dr. Walter is still panting after sitting a few minutes:

“How long has it been since we ate here?”

“Two or three months.”

“You know, it’s so familiar if you had said ‘last week’ I would have believed you.”

May remembers our conventions—she brings glasses of ice water with lemon slices, two mugs of tea, and soup and salad, which are part of the lunch special.

Dr. Walter asks me again how long since we’ve eaten here. Two or three months, I answer.

“You know, it’s so familiar if you had said last week I would have believed you.”

We go through a similar routine several times during the meal. Sometimes he begins by saying:

“I don’t remember if I’ve asked you this already . . .”

I just answer again the same way.

I see him as a friend, mostly, now. If I fall silent he’ll prompt me:

“You seem lost in thought.”

I might tell him my dream about sheltering a cat and a dog during a sniper lockdown at my workplace. He’ll listen without offering an interpretation.

He’s sympathetic about my wife’s sciatica, and how her restricted mobility affects her life and mine.

3

A giant inflated rat is outside Dr. Walter’s building on Second Avenue. The painters’ union is protesting hiring of low wage workers instead of union painters. I take a flyer and enter the building. I visit him at home since his daughter called me and told me they had to give up his office across the street, because he couldn’t get there on his own anymore.

When I arrive today he insists we eat what’s available in the fridge. His home health care aid, Gwendolyn, from Jamaica doesn’t know from pumpernickel. I point to the pumpernickel bagels and instruct her to defrost them for one minute in the microwave, slice them and then toast. She presents them with American cheese slices on each half. She makes more iced tea from instant but it is way too strong so we ask her to dilute it. Gwen now announces she is going down to the ATM and leaves the apartment.

As we are eating our bagels and cheese I try conversing. I ask about his daughter.

“Is Cheryl coming today?”

He shrugs.

I adjust the blinds behind me to let in more of the dim daylight, and then readjust the framed photos of his family lined up on the windowsill. He sits opposite me, squinting.

“Please move that one over if you don’t mind. I want to see the photo of Lila.”

Lila was his wife who passed away from pneumonia a couple of months ago.

I move the photo: “Is that okay?”

“Yes. Thank you. By the way, what happened to Lila?” he asks.

He was married to and lived with this woman for sixty years.

“She passed away a couple of months ago. She had pneumonia,” I reply.

There is a silence for about half a minute. He drums on the table the rhythm to “shave and a haircut”. I join in on the “two-bits” end. We do this when neither of us says anything for a while. He finally says: “Thanks for reminding me. I guess the shock was so great I repressed the memory.”

He still knows who I am. He tells me he thinks of me as family.

***

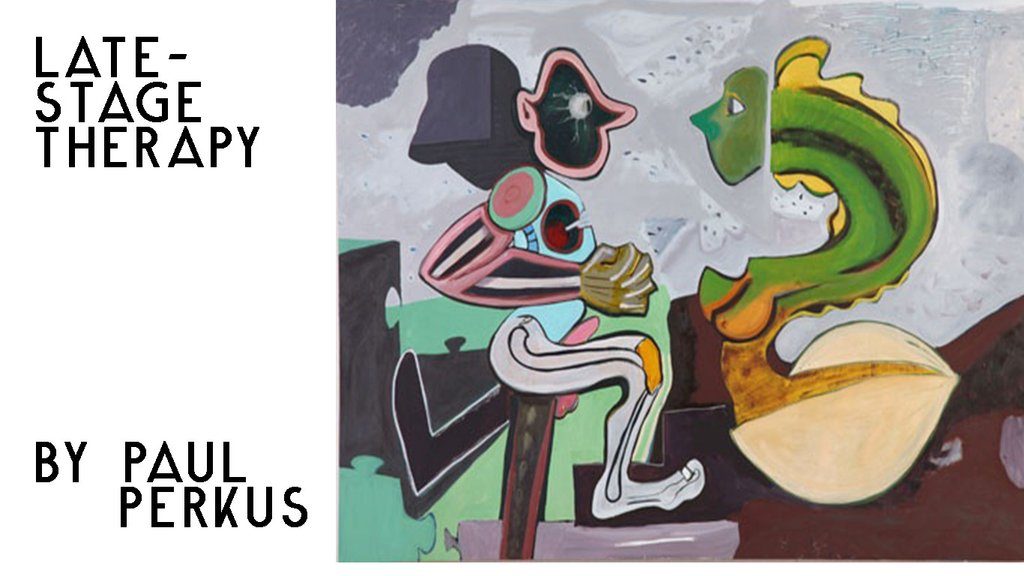

ARTWORK BY PAULINE HALPER