Snowball Jr.

By Ashleigh Bryant Phillips - Aug 14, 2019

When I was a deer I was a doe. My mother pushed me out, nuzzling a great oak tree. It was spring. There was a creek nearby. Birds were always singing: meadowlark, grasshopper sparrow, nightingales. I could hear everything better than I’d ever heard before. But I didn’t know if any loved ones from my old life were there with me. I missed them.

And I missed things I shouldn’t have. I missed the man with stubby fingers, the smell of his awful butter lube. The peach-tiled bathroom. The vibrating bed and banana pudding milkshakes. The married man who called me Mama. He patched my tires, bought me groceries. Choked me in his ill-lit apartment during Jeopardy. Mad Dawg 20/20. Omegle. Spit dangling from my lips onto his. Biting his rat tattoo.

I missed the man who looked like Bob Dylan on Blonde on Blonde. He wore paint-splattered jeans. We met in LAX. I handed him my copy of VICE. I told him to read the story “Malibu” about a man stuffing his fist into a stranger woman’s mouth. It was a night flight and I watched the top of his hair glowing rows ahead. He was reading. It was thrilling.

But when I was a deer, the wind blew and I could smell the insides of flowers far away. I could hear cars coming like oceans. I could hear bees building hives.

In the summertime me and mother ate from the soybean fields. That’s where we liked eating best. It was open and easy, delicious and nice. And in the fall when I got bigger, my mother took me into the backyards of the country people. But only early in the morning when the sky was purple-pink and dew glistened on the apple trees. My deer mother would stretch her long neck and pick apples for me. I wanted to ask her—what did she hear? But I could only communicate with her in acts of service. This had also been my language before, rubbing Khiel’s Creme de Corps into his cracked knuckles, sweeping his floor; him filming me on my knees, my first video.

I let my deer mother clean me with her soft tongue. I drank her milk so gladly.

My mother before never nursed me. She never left the bed. She grew fatter and fatter every year of my youth. She stomped when she walked. I hated it. Once, we went to Disney and the Space Mountain attendant couldn’t strap her in. She got a sleep apnea machine so the fat on her neck wouldn’t smother her at night. She fed me Little Debbie cakes and chip sandwiches. Then she got gastric bypass, slimmed down, started wearing low cut tops and eyeshadow. She jumped from job to job waitressing. She gossiped like middle school. The cooks and local policemen came by to see her on her shifts. Her necklaces got tangled in the skin tags on her neck. She begged me to mash cysts on her back. She could be so mean. She loved Prince and Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Bachelorette and Princess Di. She brought me a clean set of cotton panties when I got herpes. She didn’t read, she didn’t cook, she never cut her fingernails. Her daddy called her Snowball.

And I was Snowball Jr. I was a white-tailed deer, a doe. The apples I ate every fall were crisp and sweet. They smelled clean when I crunched them. It made my piss smell strong.

That’s when the bucks started coming, they were rutting for me.

The first time I was mounted by a buck I’d wandered far from home. I’d crossed two country roads to get to a patch of peanuts. And I laughed in my head, remembering when I was a little girl, my fat mama sat me down with a book called Where Did I Come From?

“Penis,” it said. “Like Peanuts without the T!”

The buck smelled like oily hair and piss, akin to mine just mustier. And I wondered who the buck was, if he’d been anyone before. He could have been Napoleon, Cleopatra, or Mary Magdalene. Ted Bundy or Robert E. Lee.

When the married man filmed me on my knees he said I could make a lot of money. I needed a new set of tires and my wisdom teeth removed. He took out his pocket knife and cut through my tights. But this buck had trouble balancing. Every thrust pushed my front hooves further into dirt. The land was dry and dusty. It was dark, but in my mind was like a movie, I saw a spotlight shining from behind him, the shadow of his antlers, a piercing tangle before me. I heard the nightingales singing.

After the buck finished I started running back to my mother.

I couldn’t really see, I was running so fast.

When I was little I played sick so I could stay home and cocoon myself in blankets. I’d poke my head out and watch the History Channel. As a form of meditation, Queen Elizabeth would translate English into Latin and then Latin back to English. She wrote a whole book of prayers that way. I was thinking of this, the steady stroke of her quill, when a car struck me.

I made it across the road but my insides started bleeding out of me. I fell in the lawn of a country church and a big rain came down. It fell into my eyes, onto my spongy tongue. The ground was getting soggy and I felt myself sink. I knew what would happen to me.

I’d seen it almost every day, the big black buzzards. When they got full they put out their wings and stood still as a statue, shining warm in the sun. But something I didn’t know was the sound their feathers made when they were still. The wind pushing through their tight feathers made a long, high-pitched whistle.

But when I was a doe, I wanted my ending to be different. I know it’s cliche but all I could think of was the great erotic Debussy composition. Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. And I wished I could have been listening to it there while I died. From what I remember, in the beginning, there were harps and a french horn.

_____

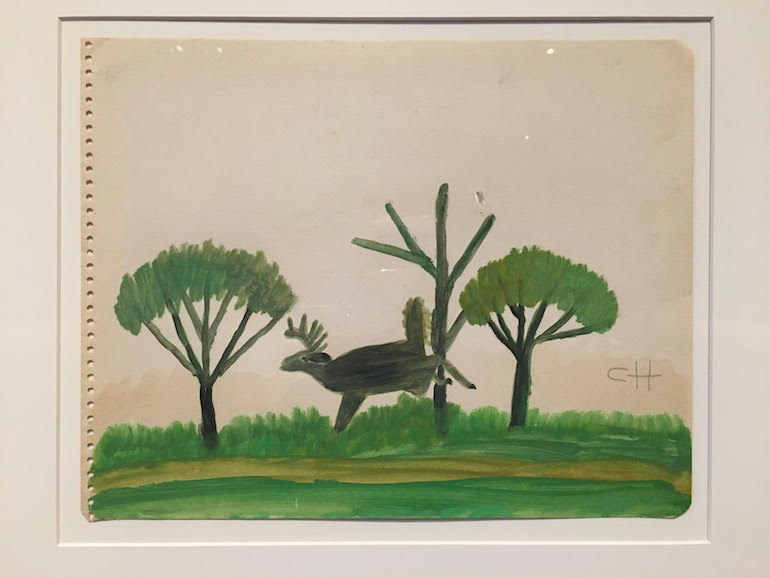

ARTWORK BY CLEMENTINE HUNTER