Egress

By David Hayden - May 18, 2018

Many years have passed since I stepped off the ledge.

I had cleared my desk, and all that I wanted to keep was saved on a memory stick placed in my top pocket. Everything else – I deleted. I found a window that I could cut and cut again to make an opening through which I could step out onto a narrow ledge, and as I moved from there into the air I felt relief, a loss of weight. I began to observe the office building as if for the first time: the honey-coloured glittering skin of stone, the terracotta panels, smooth and grooved; the sheets of clean glass. My eye and mind moved with delight from the detail to the great mass of the building and back again. I felt joy to be outside forever.

I expected to be cold but the air was mild, the speed delicious, the freshness vast and edible. I remember looking up briefly to see my fellow directors staring with alarm through the boardroom window. All except Andrew, who pinched his tie, smiled and waved.

I stopped of a sudden on the air, all my mass returned to me, seemingly in the pit of my stomach, my arms and legs flopped forward, and I gazed down to see a woman with a chestnut bob staring up – I was definitely too far away to tell it was a chestnut bob. She looked away, down at her feet or towards the door of the yellow cab that had just pulled in to the kerb, and I began falling again as quickly as before; and the cab door opened and, as she stepped in, she glanced at me again, and again I paused, juddered in the sky, and I heard the door thump closed – I was probably too far away to hear the door thump closed – and I began falling all over again with fresh delight. I sang, and the stale, old words tore away from my mouth and up towards where my life had been.

Pages flew up towards me. I caught one and read:

Forehand cross-court, faster than the eye can see and he’s on his knees crying, and the crowd are cheering, they are on their feet, and he’s still on his knees grasping his head as if to hold in the burst, the spraying contents, and his opponent has jumped the net and is standing close to, watching the victor weep. The winner’s mother and coach appear and stand around him and the weeping continues until the crowd fall silent. The defeated man steps forward and places his hand on the victor’s curly head and he calms, stills; his tears cease.

The page left my hand.

I had the idea that I should be falling at a more or less constant rate, varying a little depending on how much wind resistance I presented by increasing or decreasing my surface area; but I found that I was accelerating. And yet, after a few minutes, I could see that the ground was farther away from me than I could have expected it to be and, what is more, seemed to be receding faster than the rate at which I was falling. I rolled over and the building was peeling away to the side and I strained, against the blur, to look in through the windows to the brightly lit, open-plan floors and I saw people held in tension, faces desperate, smiling, empty, fear-struck, fulfilled, turned away. Everything was as it should be.

Many gathered coats and bags and headed for the exits. A moment later they were pushing out of three great revolving doors that face the street on the ground floor. Going home.

Homes are places made familiar through returning. Time is inside the fragrance of return, and it is not freshly-baked bread, not lemon zest, icy pine forest or mother’s neck; it is not just stale coffee, stale smoke, stale sweat, the tang of detergents, or the rich, unnameable odours of the new, old, building reasserting themselves over, and through, the everyday fug; it is the substrate that we make, alone and together, out of the stew of chemicals that our skin encloses, out of the choices we make, or are made for us, about what we take inside, what appears outside, and everything that was there before us that still has a trace that can rise. The fragrance of return is all that we did, and was done, returning to us in a moment as the door opens.

Night happened without my consideration. The sodium orange street lights and palely fizzing moon appeared according to their different causes. On every floor were lone workers, spot-lit in their cubicles or at the desks of their private offices. My office, cool and comfortable, was up on high, towards the clouds. It was the perfect situation and moment and occasion for making money by making things happen. Each working hour like the beat of a heart, fast or slow, in sinus rhythm or bumpily asynchronous, entailed with all the others in apparent continuity, but each time gone and gone and gone and gone.

People like myself, whose long-settled routines determined their simplest choices, would be retiring to their beds and while I was tired it seemed risky or indecorous to fall asleep, to sleep while falling, and I resisted until the early hours when my eyes became the only part of my body to weigh, so far to say that I felt that they were pulling me to earth, orbs to orb. For a time, I was unconscious and dreaming – all useless things – and I woke in the dawn light reaching for a blanket that was not there, with a bladder big and tight inside my belly. I rolled over, unzipped and sprayed onto the street with relief, without regret. There was a larger movement inside me and I pulled down my pants and strained it out of me and watched the brown stuff fly away and thump into the street where, I imagine, it broke into turdy pebbles. It was only when I pulled up that I chastised myself for an unclean act, and then I didn’t think about it again.

The workers were returning, many holding tall white tubes of coffee. They would join those who had stayed all night working on refractory problems, moving in minutely close or stepping back to a global distance to review risk or loss, to find resolutions that would cause money to leap free from wherever it was trapped: in bodies, components, minds or ore; in ideas, longings, irritations, bare possibilities. Everyone labouring to add more to the much.

The street was deep in snow: blank, then ridged and banked; grey and black and then clear. The bare boughs of the avenue trees sprouted curls of green that unfolded and spread wild, cloaking the wood, making buds and flowers and falling petals. The sun buried the city in heat; the star paled, lilac in dreams, scuffed yellow in the sky. The leaves turned sere, descended a scale of gold-orange-yellow-brown and flopped in fat, spicy drifts. Snow again and all was white, quiet, on the way back to green and gold and white. The smallest tremors of the sun on the air, the air pressing on the ground, the air pressing on itself – humidity from ash dry to falling ocean, heat searching and rising, swelling bodies and air. All days in one.

Cars appear bigger: shiny, brittle shells that move slowly, serried, similar amid their great variety; then smaller, faster, blips of light that never touch one another – then fewer and fewer until the avenue lies empty of all moving things except the occasional ancient bicycle – rider bent over the frame, face covered in a surgical mask.

I roll and smile to the sky. Birds with mighty, cloud-spanning wings gyre above, the sun flashes on their smooth bodies, and when I turn back I find I have dropped many floors and the ground is coming up fast. I close my eyes and count, running the numbers backwards. When I open them I find I have dropped many floors and the ground is coming up fast.

Many years have passed since I stepped off the ledge. All that I wanted to keep was saved.

_____

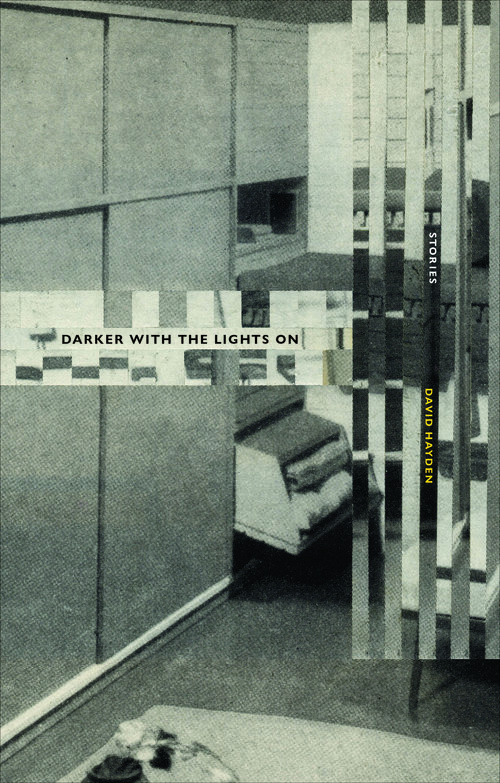

“Egress” is the first story in the collection Darker With the Lights On by David Hayden.

Click here to purchase from Transit Books in the U.S.

Click here to purchase from Little Island Press in the U.K.